One participant’s experience

Naples

Seeds

I first laid eyes on David Money in Naples at the Humanitas conference in 2007. With my friend Trudy, I had cut out on the summer course we were attending in Rome for this weeklong extravaganza hosted by Luigi Miraglia (Accademia Vivarium Novum) and I had no idea what was in store for me. No expectations can be an excellent starting position and I fell head over heels in love with a bad, bad city. Totally unattainable and very dangerous, as I discovered in retrospect. But I had a week-long fling with it, and the conference squired me around like no suitor ever has. Wined me, dined me, showed me the sights, seduced my senses and titillated my intellect. Memorable lectures, all in Latin, in the royal botanical gardens, the royal palace, the royal theater, the conservatory of music, cloister upon cloister, of course Pompeii and the archaeological museum, and many more. Candlelit concerts in cortiles, banquets among the ruins. And I was housed in a convent in the center of the oldest part of the city. The nuns would sing me awake at six or so, and then Trudy and I would repair to the Bar Nilo around the corner for our daily cappuccino and cornetto. David Money’s lecture took place in the Conservatory of Music, its cortile featuring a larger than life statue of Beethoven, coattails flapping. David enthralled his audience of about 40 people with an account of the process and products of his life-long preoccupation with Latin verse. At once comprehensible, inspiring and hilarious (all in Latin), my thought at the time was that we had to get him over here to teach us some of what he does.

Nilo

This would clearly require the backing of a wealthy institution, and a magician willing to pull together an esoteric intellectual experience for an eclectic group of people at reasonable expense just for the hell of it. I immediately thought of my good friend Gina Soter at the University of Michigan. It took a while for the idea to percolate and the ideal to take shape. A glimmer of possibility came when a small cadre of what she calls “armchair Latinists,” faithful participants in her weekly spoken Latin grex expressed interest in just this idea, an opportunity to learn the arcane practice of Latin verse composition. With a core of people interested in making the thing a success, the stars aligned with the news that David Money was on the program at Terence Tunberg’s Conventiculum Lexintoniense in July 2011. Gina began the plans for Inter Versiculos, a deft blend of lecture, demonstration, discussion, collaboration, time to write, field trips for inspiration, shared meals for cohesion.

Threshing

First, the Place

25 acres in rural Dexter, about 30 minutes west of Ann Arbor, provided the locus amoenus for our poetic labors. Lauren Kingsley, a textile artist and fly fisherman with a big background in English literature purchased Lakeview Farm about 10 years ago and with her husband has transformed it into a rustic event center, a lovely retreat with mature shade trees and vistas across rolling cornfields. Each day upon our arrival we retired immediately to the barn for an hour or so to wrangle with our hexameters as the birds and bugs went about their business in the cool of the morning. Lauren plied us with an array of home-baked goodies, local produce and a magnificent luncheon daily as she kept an interested eye on the progress of the poetry.

Class Time

The first session in our barn on Parnassus opened with an invocation to Mildred, the muse of Michigan. Was I the only one who wondered how exactly she had earned that name? Probably just as well I didn’t question, because she proved most benevolent to our efforts. David’s first lecture included a very short list of tips for composing hexameters and pentameters. Start with an idea – what’s your point? – then assemble a generous list of words that may be useful in expressing it. Build around the caesura. The third or fourth foot caesura is inviolable. SVOR: the idea needs subject, verb, object and “rubbish,” i.e. adverbs, adjectives and whatnot. Worry about everything but the rubbish first. Short syllables are harder to come by than long, i.e. dactyls are trickier than spondees, so start with the last two feet. It’s generally best to try for two and three syllable words there. No elisions near the end of the line. Be sure to leave gaps that are easy to fill (!) around the caesura. For a pentameter, the two obligatory dactyls after the caesura are the most difficult. Start there. Stay away from monosyllables at the end of the line or on either side of the caesura. He followed this up with a demonstration, calling for an idea from the group: a barn as a venue for poetry, and some relevant words to express it: faenum, granarium, stabulum, rima, foramen, capax, praebet, offert . . . Within a few minutes he had crafted a perfect little hexameter to speed us on our way:

Aditus

Voci musarum rimas granaria praebent.

Barns offer openings to the voice of the muses.

With no more than this to go on, we were encouraged to go off into some quiet corner to give it a whirl. My first efforts were club-footed at best:

Primi Labores

Verba fugacia tirones veteres modulantur;

tardipedes pedibus fallacibus haud potiuntur.

Aging beginners coax recalcitrant meters;

stumbling they give chase as the words slip away.

Holey Barn

Over the course of the week, through practice, trial and much error, the wisdom of this initial list of tips became evident. Additions and refinements of course followed. We began to appreciate some pitfalls to be avoided. Ah, the elusive short syllable. One of many astonishing revelations I experienced concerned poetic plurals, a source of endless crankiness on the part of students just starting out reading poetry. Words ending in –um, -em, -am, all completely useless as short syllables since they’ll either be lengthened if the next word begins with a consonant, or will disappear completely into an elision if the next word begins with a vowel. How many times we fell into that trap! How many times we were reduced to trolling through sections of the dictionary looking for words beginning with vowels, or disyllabic adverbs to fill a pesky gap, or compounds of verbs we had our hearts set on that might offer us a desperately needed short syllable. How many times our point disappeared completely as we were forced to trade in words that didn’t work for words that did. Vergil and Ovid, they make it look so easy!

Within the rhythm of the full days at the farm, David had a number of activities up his sleeve to keep us from going around in circles or getting bogged down. It is surprisingly refreshing to reassemble single and double hexameters of Vergil or elegiac couplets of Propertius that have been cut apart into individual words, or to devise repairs for perfect hexameters that have been tampered with by the teacher to simulate the kinds of binds beginning poets can so easily find themselves in. It is fascinating to examine excerpts of Vergil and Ovid with new understanding of the mechanics of writing hexameters. How do they handle the last two feet? What are they up to around the caesura? Where do they put monosyllables? What’s up with –que? Towards the end of the week, David coaxed some of us into trying a variety of lyric meters, noting that words that simply will not work in dactylic hexameter have new possibilities in a hendecasyllabic or an iambic meter.

Afternoon seminars focused on the long history of Latin verse composition. Threnodia, Epithalamia, a 16th century metrical treatise on the art of poetry, 20th c. Latin haiku, 18th c. yearbooks of Latin verse, the poetic output of teenagers at Tunbridge Wells, Westminster, Eton. How far Latin studies have slipped since the time when young students were routinely writing copious couplets, not to mention paragraphs and pages of prose! It is true that back then kids didn’t have to study rocket science along with their Latin, but something precious has been lost. Wits were tested in a contest where we were to arrange 7 samples of post-classical verse in chronological order. David figured out a way to make at least ten of us winners, and the prize was a short poem, freshly composed on a theme of our own choosing.

Listening

University of Michigan Museum of Art

They say poets need inspiration, and they are right. But I’m no poet, and the high school teacher in me viewed with suspicion my enthusiasm for our first foray. Field trip!! A museum for inspiration? A quaint idea? No. Another in a week-long series of revelations. The visit to the art museum was extraordinarily productive of themes for our compositions, both individual and collaborative.

The museum’s apse was designed as a sculpture gallery, but now only 2 free-standing marbles remain, meager testimony to that original purpose. “Nydia, the Blind Girl of Pompeii,” was a subject suggested to sculptor Randolph Rogers, who grew up in Ann Arbor, by a fictional character in Edward Bulwer Lytton’s Last Days of Pompeii. ‘Pompeii is burning, all is lost, and nobody can get his bearings in that chaos. Only Nydia, being blind, is able to lead Glaucus and Ione to a boat. She remains behind, unseen, and once Glaucus and Ione sail she drowns herself in the sea among her flowers.’ A placard near her describes the plaster replicas of classical marbles that once surrounded her in this huge rotunda. Times changed and their status as replicas made them no longer welcome in the museum. They were removed to storage where they eventually succumbed to the damp. Nydia became the subject of David’s demonstration of scazontes, or limping iambics:

Nydia

Heu bis sodales alma perdidit caeca

flammis et inde negligentiae causa

Alas twice, dear blind girl, you have lost your companions:

first to flames, and then to neglect.

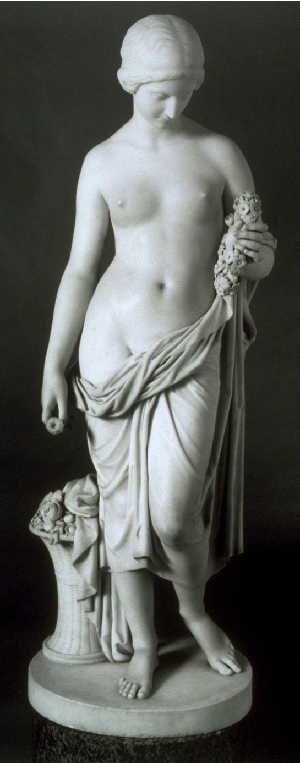

The other, a work by James Wyatt, is called “Flora” on her placard, but her flower basket is clearly stamped “Glycera.” She provided the subject matter for a group effort:

Flora/Glycera

Flora geris sertam moribundam, veste recincta

nomen sed Glycerae dulce puella tenes

Flora, your bouquet is wilting, your robe unbelted,

but the name that’s for you, girl, is “Sweet Thing.”

My own couplet about a piece in the museum involved a gilded mantle clock dedicated to Venus. On it was a priestess and a Cupid preparing to immolate a little dove on the altar of the goddess:

Venus’ golden mantle clock

Laetitiae genetrix Venus aurea, parva columba,

te caesam subito poscit et hora fugax

Translation

Little dove, golden Venus, the mother of happiness,

and the fleeting hour demand your immediate death.

My Clock

Public Reading

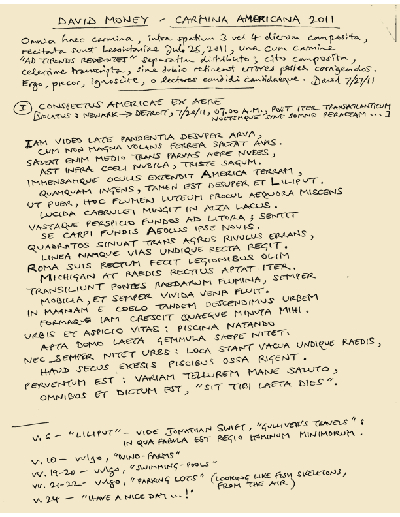

Just over the halfway mark, the public was invited to the Residential College’s Keene Theater for a sampling of what was going on out in Dexter. David chose light, accessible fare for this event, much of it recently composed and still in longhand on the handout. Most everything was shot through with his wry, ironic wit, and subjects included tributes to friends, cats and platypuses, responses to poets, the scourge of hay fever, Dawn from the night owl’s perspective, Americana, the pentameter gone wild . . . the one that had us all pink about the ears and forehead was “Stipula,” an ode to his five-o’clock shadow. Another that struck a special chord with me was inspired by the view from the airplane on his approach to Detroit. Streets in grids, streams cutting curves across them on their way towards the lake; weekend empty parking lots, their white lines like bleaching fish bones. The poem captured one of many sources of sadness I feel about my country, this particular one arising from watching more and more of suburban America disappear under blacktop. Four of our number answered the call to read their own creations from the workshop. From the reading we adjourned to the glorious Kelsey Museum with after-hours access to the exhibitions.

Fish Bones

Gone Fishing

On Friday morning we set out on foot to the trout farm across the street to catch lunch and another form of inspiration for our poetry. I was dubious about the latter, and this time complete inexperience coupled with a little squeamishness mitigated my enthusiasm for another field trip. But I wasn’t about to miss out on any bit of the extraordinary adventure this week was shaping up to be. This excursion as it turned out was every bit as productive of verses as our trip to the art museum had been. It pushed, pulled and stretched us in unexpected directions, broke down barriers, let off steam, delighted and appalled us all at once. On one side of the pond, a hysterical vignette involving a worm. No way to keep up appearances when faced with breaking off a piece of wriggling worm for your hook.

Elsewhere our youngest member and our only vegetarian quietly dropped her hook into the water and pulled up the first fish. All flocked to her side for instruction. A soft-hearted carnivore couldn’t bring herself to fish, but compassionately stood by to move catch buckets out of the burning sun. Soon she was carrying our catch to the reception counter for speedy beheading.

A lasting moment occurred for me when we had to call over a staff boy to extract the hook from one poor fish. In the process blood spewed all over Britta’s white tee shirt:

Fish story

Piscatricem hamo piscis non prodis inhausto,

sed tunica indicat sanguine tincta nigro

Translation

Oh fish, having swallowed the hook, you don’t betray the girl who caught you,

but her shirt, stained with black blood, tells all.

None of this interfered with our appetite in the least; the fish Lauren grilled for our lunch vanished in seconds, and the verses kept on coming.

Bloody Shirt

Hospitality and the Kitchen

While the only stated prerequisite for the workshop was a solid grasp of Latin grammar, that doesn’t begin to address the problem of cohesion. From the festive dinner at her house on the first evening, and even before, when she coordinated transportation to Ann Arbor, Gina established such a genuine and powerful atmosphere of welcome that it was impossible not to become involved in the success of the endeavor. Day after day, the group arrived punctually, mixed and mingled, paid exquisite attention, stepped up for chores, donated goods and services, tried everything.

Seven of the participants came from far away and for them and anyone else who cared to join in, Gina was determined to keep up a steady stream of dinners throughout the week. This turned out to be from 10 to 12 people each night. I arrived primed to do all I could to facilitate this agenda. Gina traded in her organizer hat for a chef’s toque each evening. Tina ‘no chore too gross or dainty’ Salowey signed on to the mission and brought another grand layer of fun and skill with the grill to the kitchen detail. A steady stream of volunteers rolled up their sleeves to peel potatoes or pluck parsley. Still and all, with the workshop running until 6, add the drive from Dexter and a stop at the grocery store, we were hard pressed to get dinner on the table before 8:30 or 9, and this left plenty of time for getting acquainted.

My preoccupation with the food became the subject of my longest poetic effort, one that meandered pointlessly for days until I thought of a mildly clever way to resolve it. Thinking I had prevailed I showed it tentatively to the master only to discover that the last line had an extra syllable in it. Despair! I threw myself on his mercy and watched as David made two neat little incisions, rearranged a couple of words, changed a tense and voila!

The Dinner Detail

Quisquilias removet purgatque ancilla culinam:

anxietas cenae subito perpellit acuta.

“Heu,” clamat, mox subsidium fert Vesta puellae.

Auxiliante dea pavor hic evanuit. Ecce

carbone in calida stridens instigat orexin

salmo. Intrant alacres recitantes scripta poetae.

Et versus salibus ventrem et farcire volebant.

Translation

She takes out the garbage, and scrubs the place spotless,

But what about dinner, the kitchen maid worries.

“Poor me,” she beseeches; the kitchen gods hear her.

They come to her aid and her courage returns. Soon,

salmon a-sizzle on coals rouses hunger.

Poets composing are drawn to the feast,

hoping to season themselves and their verses with wit.

Fixing the Rice

The Mix

11 men, 7 women, 1 knew almost everybody, 8 knew almost nobody, 10 taught Latin, 3 full-time students, 1 stockbroker, 1 retired librarian, 4 over 60, 4 under 30, 3 tenured professors, 3 entering the profession, 2 public high school teachers, 4 affiliated with the University of Michigan, 11 Michigan residents, 1 Australian, 2 Brits, 1 expat, some Catholics, some atheists, each unique, all Caucasian. Varied? You be the judge.

Britta

David Money’s lifelong dedication to Latin poetry has resulted in a rare seed. Gina Soter’s concept of Inter Versiculos was to provide the best possible environment and conditions for that seed to germinate on American soil. The workshop was ambitious and varied: three primary locations, full board, low cost, part formal, part informal, excursions, participants from here, there and everywhere, housing as needed, planners as players, long, long hours. In short, there were many logistical details to coordinate, many places to fumble, to lose the rhythm or the momentum. Our week was blessed by the presence of a tutelary deity in the person of Britta Ager who stepped into the amorphous and open-ended role (and hours) of “assistant” with multi-faceted competence, attentiveness and willingness to do whatever was needed to pull off the next feat. From airport pickups and daily transportation to assembling a reference library to producing handouts to removing fishhooks, Britta’s contribution to the smooth working of the workshop cannot be overstated.

Library

The Last Huzzah

Who better to affirm our accomplishments of the week than each other? Management had this built in from the start. Last formal session, Saturday afternoon: poetry reading by and for participants. Gina and I also had a banquet to plan, so we skipped out to a nearby farm to buy corn and anything else that looked good. Gladiolas, looked great. We bought a huge bouquet of pink and purple ones to grace this momentous occasion. The stage was set with the flowers stuffed into a watering can and a homely painted backdrop of Venus on the half-shell. The video camera promised to record one awkward moment for every sweet one. Our host Lauren was there with bells on – she dressed up for the occasion. Lovely. It was loosely organized. Jump up when you feel like delivering. I, with my week’s total of 13 big ones of dactylic hexameter and elegiac couplets, inserted myself early on in the lineup. You had to be there. You should have been there!

Thank you to the University of Michigan for making it possible, thank you Gina, David, Lauren K., Tina, Britta, Peter, Paul, Petrus, RJ, Oswald, Tim, John, Christine, Anthony, Laura, Lauren C., Michael, Patrick, for making it unforgettable.

Karla Herndon

October, 2011

Albany, California

Glads